A Marxist organisation needs a political program which contains both minimum (or immediate) demands and a maximum vision of the future, argues David Lockwood.

A Marxist group cannot approach people on the basis of one issue at a time and then, through an accumulation of such issues, hope to see a spontaneous eruption of revolutionary consciousness. However, this is the practice of many left groups.

These groups approach mass politics by setting up the Campaign For X, or the Action Committee Against Y, or Workers Against Z in the hope that during the struggle against X or Y or Z, participants will come to the True Light. In my experience, this rarely happens – or when it does, recruitment of ones and twos results from the organisation’s cadre sitting down with the activist and explaining the real nature of the struggle (‘socialism’) and the real task at hand (join my group).

In order to break beyond such sect practice, the workers’ movement needs a broadly accepted revolutionary and democratic program that, from the outset goes beyond single issues, that explains the nature of the society that produces the problem and outlines the nature of the society that can solve it.

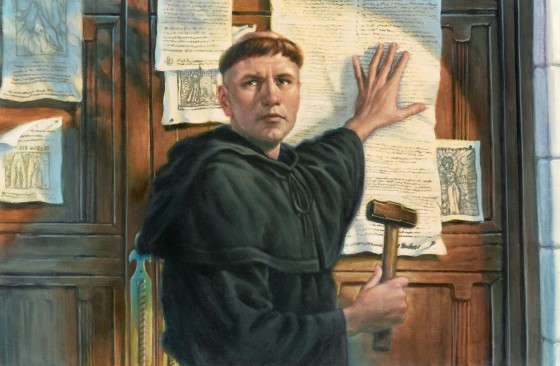

Anything else is an exercise in sleight-of-hand – a way of masking the real (communist) program with a series of temporarily popular and/or radical sounding slogans. In The Manifesto of the Communist Party, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels declared “Communists fight for the attainment of immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; but in the movement of the present, they also represent and take care of the future of that movement.”

Such a program should contain a number of immediate or minimum demands – about which I’ll have a bit more to say down below. You can find an example of this in The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier (1880), by Marx and Jules Guesde. It’s worth noting that, once written, the two authors fell out over the meaning of the immediate demands. Marx regarded them, taken collectively, as a road map for the workers to take power. For Guesde, they were there as ‘mere slogans to shout in order to inspire mass strikes that would throw up workers’ councils.’ (‘The revolutionary minimum-maximum program, Donald Parkinson, Cosmonaut, May 2021) Take note, Action Committee for Y.

Finally, it is the program that shapes the political organisation and its strategy. A communist party is based on Marxist unity around the acceptance of such a program. It does not imply slavish devotion to every sentence, nor should it contain ideological faith or tactical shibboleths to trap the unwary. It is a kind of roadmap, within which strategy and tactics are debated.

The programs of classical revolutionary social democracy (Communist Manifesto 1848, Parti Ouvrier 1880, Erfurt Program 1891, Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party 1903) contained a maximum and a minimum section.

In his accompanying explanatory pamphlet to the Erfurt Program, The Class Struggle, Karl Kautsky wrote:

The program adopted by the German Social Democracy at Erfurt in 1891 divides itself into two parts. In the first place it outlines the fundamental principles on which socialism is based, and in the second it enumerates the demands which the Social Democracy makes of present-day society. The first part tells what socialists believe; the second how they propose to make their belief effective.

Karl Kautsky, The Class Struggle (Erfurt Program)

Looking at the maximum section, British communist Mike Macnair says that it outlines “the general idea of communism as a society without classes, state or family as an economic institution, in which production is collectively managed for the human good, and explain[s] briefly why this sort of society is becoming possible, but can only begin to be attained through the working class … taking over the running of society”. (‘Transitional to What?’ Weekly Worker 1 August 2007)

The minimum program is aimed at the creation of a political framework that establishes the rule of the working class and the possibility of economic transformation. It also puts forward immediate economic demands. Those demands do not yet constitute full socialism – they may well be consistent with the continued existence of money and commodity exchange. The individual demands of the minimum program could be conceded by capital. But if the minimum program as a whole is to be implemented, political power would have been transferred to the working class. Revolutionary social democracy, therefore, refused to participate in governments that would not implement the minimum program in its entirety.

As mentioned above, the minimum program is not a set of slogans designed to encourage workers into struggle and through that struggle, to bring them into confrontation with the capitalist state, though such struggle may well do so. Nor is it a way of tidying the unfinished business of the bourgeois revolution (as was widely believed in the later years of the Second International) – which would imply the possibility of a better capitalism.

Comintern and Fourth International – both wrong

In the first half of the 20th century, the Third International, followed by the Fourth, declared that the necessity of minimum and maximum programs had been superseded – due to the world revolutionary crisis. This remains the position of much of the Marxist left today – though without the crisis. In the resolution on Tactics adopted at the Comintern’s Third Congress (1921), “the present epoch is revolutionary precisely because the most modest demands of the working masses are incompatible with the continued existence of capitalist society”. The Comintern therefore put forward ‘concrete demands’ which would draw people into struggle. Then, presumably spontaneously, “the working class will come to realise that if it wants to live, capitalism will have to die”.

In 1938, Trotsky’s Transitional Program argued that the crisis meant that the simple defence of wages, conditions and rights would bring about class confrontation and the working-class conquest of state power.

Understandable perhaps in 1921 and 1938, but still wrong then. But this approach has now been falsified by intervening history and is very wrong today. In many ways it is a return to Guesde. Macnair writes:

[This] radically false strategy is the strategy of the general strike, the attempt to move directly from the economic strike struggle to the ‘social revolution’ … without directly addressing the question of the state or passing through the political struggle under capitalism. (‘For a Minimum Programme!’ Weekly Worker 29 August 2007)

These scenarios described by the Comintern and the Trotskyists (and adhered to today by most of the modern Marxist left) rely on the consciousness of the unorganised masses being spontaneously transformed through (usually economic) struggle into revolutionary consciousness (with the help of a handy copy of the revolutionary paper).

From the first steps of a wage rise dispute or defence of a community centre, through to a generalised strike wave, the workers are somehow meant to leap to the need for workers’ councils and their own state.

But in such a scenario it is hard to know what that revolutionary consciousness consists of (beyond the inevitable workers’ councils). The result is usually an opportunist hodge-podge of minimal demands, while the ‘real demand’ of soviets are kept for Sunday School speechifying among the anointed membership. But the working class cannot be tricked into taking political power.

Completely missing is the conscious act of the working class to win political power against the existing state and constitution in order to carry out its minimum demands; absent is a political struggle for the minimum and maximum program.

That is why the struggle to win the existing left and the broader labour movement to the programmatic approach of a revolutionary-democratic minimum-maximum program is a burning priority for Marxists.