In the footsteps of the ones who’ve gone before, from Pemulwuy to the present day: a long read

Bob Makinson is a former member of the Communist Party of Australia and a peace activist member of the SEARCH Foundation. He recently delivered this talk to a group of anti-war activists in Sydney. He acknowledges the Cadigal clan of that area, who are traditional owners of unceded land.

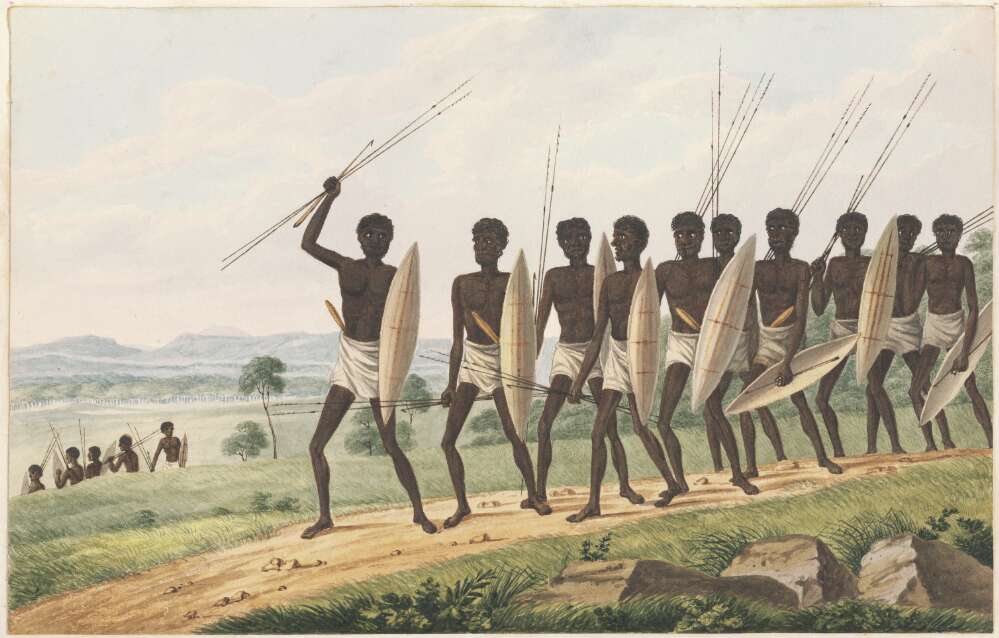

After the initial shock of European arrival in 1788, from 1792 to 1804, some Cadigal people, survivors of the smallpox epidemic of 1789, joined with their Bidjigal kin from a bit further out, under the military leadership of Pemulwuy, as did warriors from the Dharug and Tharawal clans. They were part of the first military actions – the first resistance war – after the European arrival. An anti-colonial war.

They were alert to the political dynamics of the newcomers, and were prepared to utilise them. They were receptive to some escaped convicts, both English and Irish (and some of those were recent veterans of the Irish uprising of 1798), and had nuanced non-hostile interactions with some of the other colonists. Collaboration across the lines arises from common interests.

I’d also like to acknowledge and honour other people in our collective history, people with relevance for us today trying to find the means to prevent war.

Early years: from Quakers to the Boer War

The earliest organised ‘peace’ formations prepared to swim against the colonial tide in Australia emerged in the 1890s and early 1900s. They were not all, or even mostly, left-wing groups in any clear political sense.

So, I’d like to acknowledge two of the early organisations active for peace that are still with us today.

I acknowledge the Quakers, who had been religious dissenters in Britain, and advocates of both peace in Europe and the abolition of slavery. They were active anti-militarists, and advocates for the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 – parallel treaties to the now better-known Geneva Conventions. The Quakers, in small numbers, had something of a national presence across eastern Australia by the late 19th century, and were significant players in the period leading up to the First World War. There is some good material on the Quakers Australia website about the peace movement of this period, as well as contemporary anti-militarism resources, including a new report on Australia’s role in the arms trade.

And I’d like to acknowledge WILPF, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, founded in 1915 and a constant in the peace movement down to the present day. They too have been a group of consistent peace activists for more than a century.

About 20,000 to 25,000 Australians fought for the British in South Africa in in the Second Boer War of 1899 to 1902. This war saw the second use in modern history, by the British, of concentration camps. I acknowledge the Australian opponents of involvement in the Boer War, ranging from the relatively respectable Anti-War League in Sydney, across a wide mix of republicans (many of them Irish) and Australian nationalists (many of them racists), but also small radical socialist nuclei, influenced by the Second International’s anti-war and anti-militarist stance.

Tom Mann, Engels and the Second International

That socialist influence was strengthened in the following years by the growth of unionism, and by the seven-year whirlwind presence in Australia of British unionist Tom Mann, from 1902 to 1909. Among other things, Mann co-founded the Victorian Socialist Party, a precursor to the CPA. His focus in Australia was on industrial issues and labour movement political representation, but he also preached anti-militarism, and was heard. He was later a foundation member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Internationally, I want to acknowledge Friedrich Engels, who in 1887 ‒ a whole quarter of a century before the outbreak of the First World War ‒ made one of the most far-sighted predictions in the whole Marxist canon. It is worth quoting at length:

“And, finally, the only war left for Prussia-Germany to wage will be a world war, a world war moreover of an extent and violence hitherto unimagined. Eight to ten million soldiers will be at each other’s throats and in the process they will strip Europe barer than a swarm of locusts. The depredations of the Thirty Years’ War compressed into three to four years and extended over the entire continent; famine, disease, the universal lapse into barbarism, both of the armies and the people, in the wake of acute misery, irretrievable dislocation of our artificial system of trade, industry and credit, ending in universal bankruptcy, collapse of the old states and their conventional political wisdom to the point where crowns will roll into the gutters by the dozen, and no one will be around to pick them up; the absolute impossibility of foreseeing how it will all end and who will emerge as victor from the battle.

Freidrich Engels

Only one consequence is absolutely certain: universal exhaustion and the creation of the conditions for the ultimate victory of the working class.

Introduction, in S. Borkheim, ‘In memory of the German Death-Patriots [of] 1806‒1807’, Hottingen-Zurich, 1888.]

This remarkable prediction came appallingly true – except for the very last item.

I acknowledge two other socialists of the time who in similarly stark terms correctly characterised the ultimate choice that faced the world then, and still does. Karl Kautsky coined the phrase ‘Socialism or Barbarism’ in 1892; and Rosa Luxembourg gave it new life in her anti-war tract The Junius Pamphlet of 1915. It has become a watchword of several socialist currents.

Socialism or barbarism

It can be argued that the fundamental event of the 20th century was not the Russian Revolution – not yet – but the catastrophic event that preceded it: the First World War. Engels’ prediction was proved, in horrible detail. Forty million dead (plus 50 to 100 million more in the associated famines and the Spanish Flu epidemic). How much human potential the world lost, in that needless war.

This was the war that proved the socialist thesis that capitalism, even when globally triumphant, inevitably leads to war, and is the enemy of humanity. It was also the war that simultaneously blew the socialist movement of the day apart along its lines of weakness – subordination of the socialist parties to national capitalist interests and their version of patriotism. It was the war that completely reshaped Europe right at the pinnacle of its global supremacy and saw the fall of thousand-year-old power blocs to new political forms – including the first serious attempt at a socialist model.

So ‘Lest we forget’ holds a very different meaning for us than it does for the chauvinists, who persecute any account of that war other than their own. We should acknowledge and never forget all the dead from that most useless of all wars, and the lessons that they left behind.

I acknowledge the war-resisters and conscientious objectors of the First World War, whose lives were blighted by their stand for principle.

I acknowledge those who in Australia worked and voted to defeat the two conscription referenda of 1916 and 1917.

I acknowledge the mutineers in the Australian Imperial Forces, in training camps at Casula in 1915 and in France in 1917, and in multiple active-service units on the Western Front in 1918. They had had a gutful, and had the courage to say ‘no more’. As did many more mutineers in the British, French, German, Austrian, Italian and Russian armies in the same conflict, many of whom were shot for doing so.

The lessons of the Great War

I acknowledge the many service personnel who returned from the First World War with varying, sometimes slowly developing, anti-war convictions, and all the wrenching conflicts of felt loyalties and life experience that they underwent during the war and afterwards – including, for the vocally anti-war veterans, repressive gagging by government and ex-service organisations.

We should all acknowledge the hundreds of Australians, and tens of thousands around the globe, who in the years immediately after the First World War chose to break completely with old loyalties to country, King, religion, and party, and to affirm a new, higher loyalty – to humanity at large, and to the world’s working class, across the old barriers of nation and ethnicity. Their decision shaped the rest of the century.

We should acknowledge and share their conviction, from the experience of 1914-18, that war is to the benefit of capitalism and intrinsic to it, and that a fundamental, central task of socialists is to oppose all attempts by imperialist and capitalist countries to wage war. That was bred in the bone of internationalist socialists from 1870 on and reaffirmed by the First World War.

But it is a military adage that the lessons of the last war are an unreliable guide to the next, and the same is true in political struggle. And so, most of those immovably anti-war socialists quite soon found that, after all, things were more complicated. There were anti-colonial and national liberation wars – relatively few at that time, but China and Abyssinia (Ethiopia) were early cases with international impact. And by the late 1930s socialists in the western countries were caught between advocating rearmament against pending fascist aggression, and seeking non-military means of avoiding the coming war. And before long they were confounded by history, and found that their new loyalties now dictated that there were some exceptional circumstances – the global threat of fascist barbarism – that justified a military convergence with some of the capitalist powers after all, as perilous as that road was to be. The great majority of Australian and world socialists worked and fought within that alliance, at least from June 1941, for the military defeat of fascism.

Hard choices, back then; they only seem straightforward in hindsight.

Contradictions of post-WW2 peace movement

And after World War II, we can acknowledge and understand, if not share, the belief of most communists of the 1940s and early 1950s that identified peace wholly and exclusively and unconditionally with defence of everything the USSR did – even while we scream at them, from this end of history, that this was a trap for our movement that should have been avoided.

But I certainly acknowledge and respect the dedication and creativity with which that generation of communists, ALP socialists, and others, after World War II, nevertheless built a peace movement in Australia under far more adverse political conditions than we face today. They realised the qualitatively new level of threat to humanity that atomic weapons had introduced and did more than anyone else to bring that threat into public consciousness.

As part of the international ‘peace front’ and the Ban The Bomb movement, they kept up a challenge which unquestionably hampered the capitalist war drive. Among other sectors, let’s remember the unions and union members – teachers, wharfies, seamen, brickies, and others – who made peace union business in those years.

Those activists were constrained by the Cold War, and by the domestic political repression of the 1950s, and (in the case of the communists) by their insistence on an uncritical attitude to the Soviet Union. They were able to build a solid but politically narrow movement that could survive and have an influence under those conditions, but ultimately could only enjoy some ‘defensive success’.

Vietnam war and the anti-militarist struggle

As Alec Robertson put it in a 1970 article reviewing the history of the CPA in the peace movement that began to change with the Vietnam War.

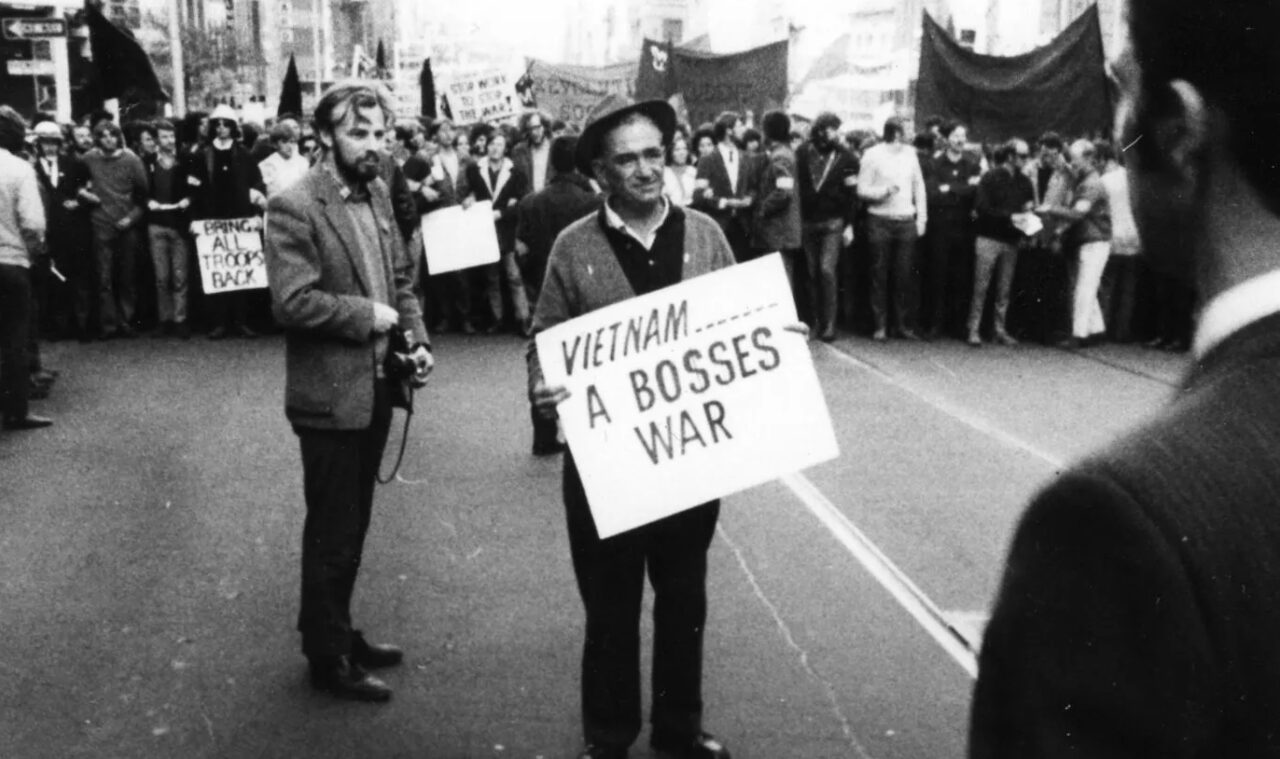

I have long been in awe at the insight with which the emerging new leadership of the CPA identified, in the very early 1960s, how the American intervention in Vietnam, then only in its infancy, would be the defining political struggle of the decade. And at how they set out, with other forces, to build a broad anti-war coalition that within a few years changed the political and cultural landscape in Australia.

As Alec Robertson wrote in 1970:

The big-scale intervention [i.e. of the US and Australia in Vietnam in 1965] … fundamentally changed the situation of the Australian anti-war movement, which thenceforth was operating in a country with a military combat involvement in a clear-cut, imperialist, counter-revolutionary war.

Alec Robertson, ‘CPA in the Anti-War Movement’, Australian Left Review (No. 27 Oct-Nov 1970)

The ‘theoretical’ anti-war struggles of the previous 15 years were finished.

And because Vietnam also brought with it the spread of dissent, youthful scepticism and radicalisation, and the emergence of significant left groups other than the CPA itself, 1965 also meant that the long night of CPA defencism was ending.”

Robertson also acknowledged the relative decline of CPA preponderance in that movement as the other forces grew, but he noted the increase in the quality of the CPA’s work and influence as it moved rapidly to an independent stance across the board – that is, independent from the USSR, and from some of its own previous practice – and opened itself to new forces and energy from below.

And Robertson dwelt at some length on the complexity of encouraging and fostering a broad movement and its evolving organisational forms and conflicting priorities and slogans, while at the same time trying to avoid the many traps that beset such a movement – and all the while seeking to project a non-dogmatic socialist view of the situation into a very non-socialist context.

Conscription, and the rapid expansion of the tertiary education sector with considerable freedom of organisation on campus, were both huge factors in the Vietnam period. I acknowledge all those who stood up to protest against that war. And as the movement did at the time, I acknowledge the conscientious objectors, the active draft-resisters. I acknowledge the mothers who formed the Save Our Sons anti-conscription organisation,

Why do we not celebrate the courage and roles of these war resisters every year? Why have we not erected our own anti-war memorials and events?

I acknowledge also the small number of veterans who organised against the Vietnam war – a phenomenon much more pronounced in the USA than here in Australia, but an important one to bear in mind in the current situation.

The energy unleashed by the Vietnam struggle defined and invigorated two political generations in Australia, and is not quite exhausted yet.

A new, large generation of young people, many of them with experience of the anti-war protests, moved from the inner cities to the suburbs, or from the cities to regional centres and areas. Many took their politics with them, and this opened possibilities down to the present day, despite the decline of labour movement organisations in regional Australia in the 1970s and 1980s, and laid a basis for a peace movement resurgence in the 1980s.

The shadow of nuclear war: the 1980s

But the years from 1972 to 1980 did see a collapse of the ad hoc, largely unstructured broad peace movement alliances of the Vietnam War period. As so often with protest-based movements, we were not good at building for permanence. There was a lot of rebuilding to be done when the acute threat of nuclear war ramped up again in the Reagan period as the US found its bearings after their Vietnam defeat, and a very sharp threat of nuclear war emerged very rapidly.

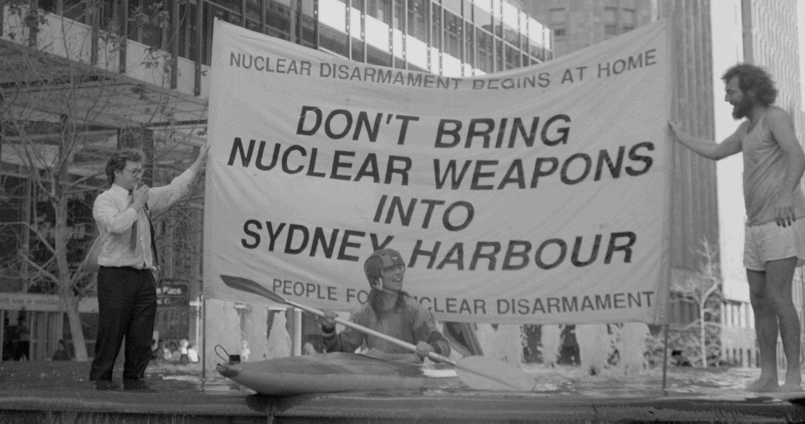

But the movement’s slump had been short enough that we didn’t quite have to start again from scratch, and I’d like to acknowledge that hard core of experienced peace activists across many organisations who pulled things together again within a short span of years and built an even bigger and broader alliance.

Something else had been happening that helped pull things back together. For one thing, the campuses were still active, although the student left had taken some severe hits. But on-campus and off, two new movements had emerged, unleashing a lot of growth-oriented energy: the second-wave feminist movement, and the parallel environment movement (in Australia, especially the anti-uranium mining movement).

So, let’s acknowledge all those movements and their activists, because what became a huge nuclear disarmament movement by the mid-1980s owed a lot to them.

And I acknowledge, for the last time in this context, the slowly dying CPA, as it had the guts and insight to reverse its previous vaguely pro-nuclear power policy, to work to unite the energies of those movements and the more classical peace organisations, and to take on and help win the fight for ‘Disarmament East and West’ as the movement’s dominant line, despite trenchant opposition from the pro-Soviet Australian Peace Committee, which was dominated by the Socialist Party of Australia. The resulting broad nuclear disarmament coalition brought hundreds of thousands of people into demonstrations in 1982 to 1985 (at peak, an estimated 200,000 people in the Sydney Palm Sunday rallies).

Equally importantly, it stimulated the emergence of a wave of semi-autonomous peace organisations in suburbs and regional centres across much of Australia, including in places that had seen no overt left-wing activity since the early 1950s.

Moving beyond the ‘long night of the left’

But with the left and labour movement organisations themselves entering steep decline, we didn’t warehouse the critical nodes of that movement, to prepare it for the collapse of protest activity after the Gorbachev-led relaxation of nuclear tensions. The similarly huge demonstrations of 2003 against the impending US-led invasion of Iraq were perhaps the last kick of that movement.

People have stayed active ever since, but from that point on, the trajectory until very recently was one of organisational decay.

After the long night-time of the Australian left since then, 30 years going on 40, we are left today with many small, rather fragmented organisations, almost all with an old demographic (except on the Palestine solidarity front), and all trying to find traction in the new period of acute war danger.

An appraisal of the social and organisational basis for a renewed anti-war movement, and a growth-oriented action plan – or plans – are our order of business.