As the 50th anniversary of the Dismissal approaches, David Lockwood urges you to maintain your republican rage and enthusiasm.

“Labor will work toward establishing an Australian republic with an Australian head of state.”

(2023 ALP National Platform. Chapter 6, 8b.)

Except when it doesn’t.

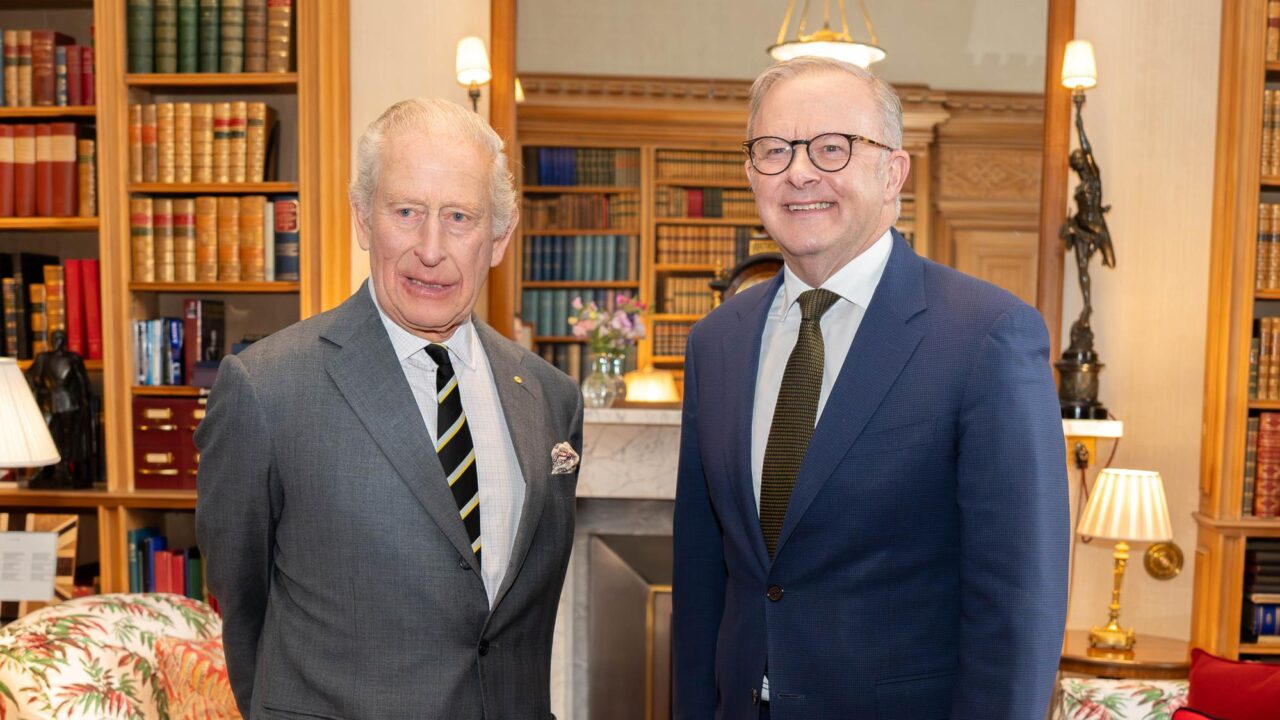

In the middle of his recent 11-day overseas tour, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese found time to drop in on Australia’s head of state, King Charles III, at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. After what was, no doubt, a splendid (though suitably modest) lunch, he told reporters that he had not broached the subject of Australia becoming a republic with the King. He said his government had more important issues to worry about. “The existing arrangements are in place,” he sagely remarked.

Further, Albanese ruled out a republic not just this term or next, but at any time while he occupies the Lodge.

“I think I’ve made it clear that I wanted to hold one referendum while I was prime minister, and we did that, and that’s it,” he told ABC’s Insiders program.

“We did that. And I think we’re concentrating on cost of living, and I’m making a real, practical difference to people’s lives.”

And that, apparently, is that. Inspiring – and revealing that the liberal elite has a completely pinched view of what a republic is.

It was not always thus. In the recent history of the ALP, a push towards ‘official’ or respectable republicanism was strongest in the 1990s. Prime Minister Bob Hawke declared in 1991 that a republic was ‘inevitable’. His successor, Paul Keating established a Republican Advisory Committee. Its 1993 report foreshadowed a republic by 2001.

This enthusiasm was encouraged by a burst of optimism in Australian capitalism. Hawke and Keating had steered the Australian economy away from protectionism in line with a global OECD shift from Keynesianism to monetarism. The Labor governments were also able to head off any potential resistance by unions through the class-collaborationist Accord.

Our rulers, both economic and political, were confident enough to endorse a minimal constitutional change – with everything done through parliament, vetted and petted by the great and the good from go to woah.

Keating told the nation in June 1995:

“As never before we are making our own way in our region and the world. For us the world is going – and we are going – in a way which makes our having the British Monarch as our Head of State increasingly anomalous.”

This white-hot enthusiasm was dampened by Labor’s election loss in 1996. Nevertheless, John Howard’s conservative government proceeded to hold a partially elected ‘constitutional convention’ in 1998 and (smelling blood) organised a referendum for a minimalist republic in November 1999.

It was a total defeat. Asked to choose between the unelectable and the unacceptable minimalist model, in which a chosen president would retain royal prerogative, the republican camp split. Howard, an arch monarchist, knew that he who chooses the question can manipulate the answer. A referendum for change to prevent change.

As we know, there’s nothing like a referendum defeat to send the Labor Party leadership scuttling back into its corner and casting around for other things to talk about. But traces of the official republican position remained.

In the 2007 election campaign, Kevin Rudd suggested another referendum, but having won decided it was ‘not a top order priority’. In 2010, Julia Gillard said she favoured a republic but that we now had to wait for Elizabeth II to depart (presumably not to upset her in this life). Seven years later, Bill Shorten declared that there would be a plebiscite and a referendum if he were elected. But he wasn’t.

The official ‘Australian Republican Movement’ ran a campaign for a referendum once the much-respected Elizabeth died, falsely expecting a surge of republican sentiment once Charlie was on the throne. The opposite has happened, of course.

And yet, when Albanese was swept to power, he appointed an Assistant Minister for the Republic – as though it were something under active consideration. Only to be contemplated after Elizabeth’s death, naturally. This occurred, as it does to us all, in September 2022. But in his 2024 reshuffle Albanese abolished the position and a year later put the King’s mind at rest over lunch.

Why is this important?

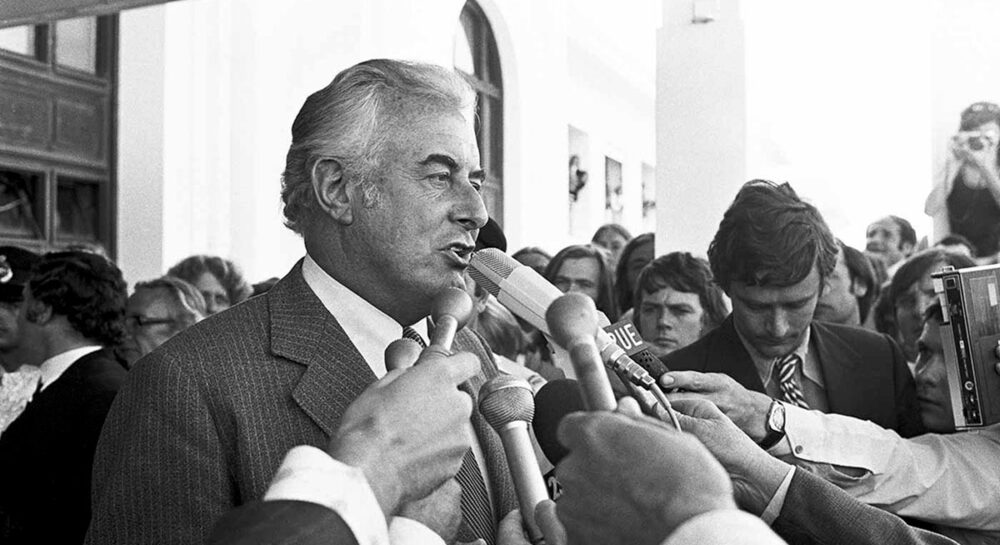

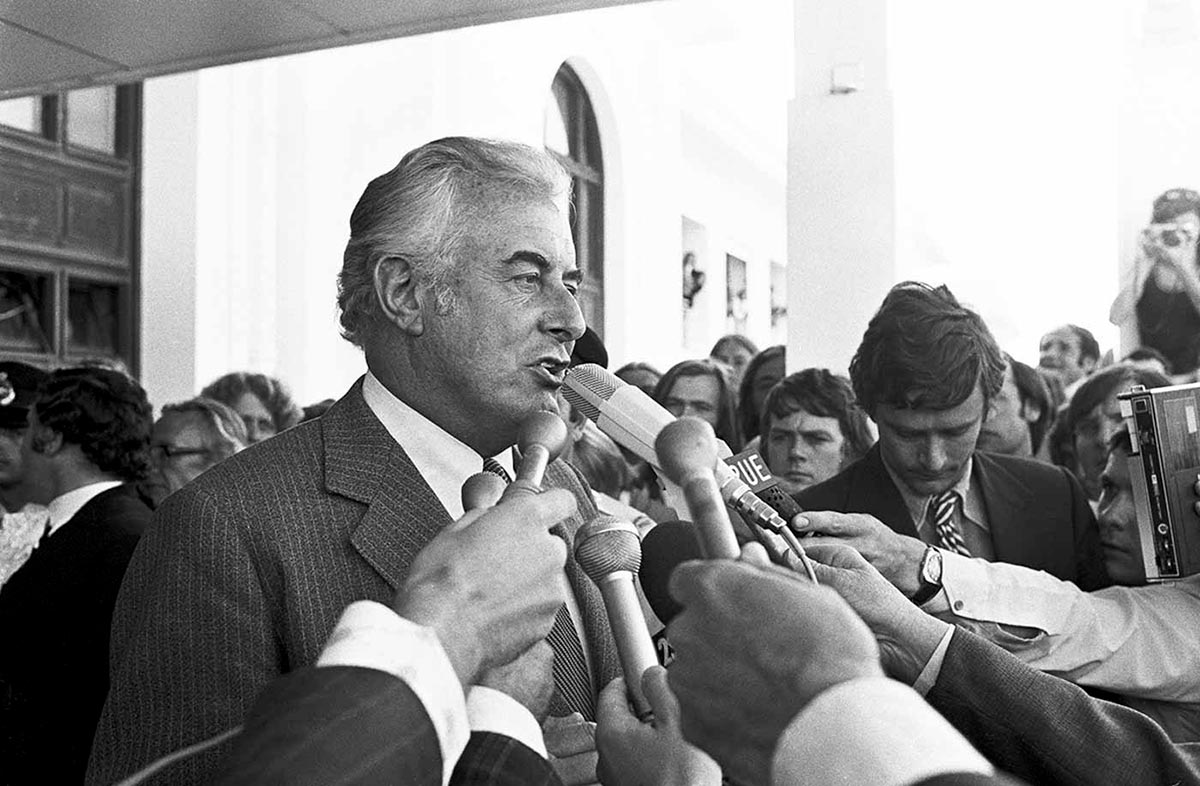

We are rolling towards the 50th anniversary of 11 November 1975 – when the Queen’s appointed representative (the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr) dismissed the duly elected Whitlam Labor government and appointed a minority government from the Coalition parties.

The Royal Family’s fingerprints were all over this decision, as proved by the recently released correspondence between the monarch and the Governor-General. But she was not alone. Australia’s capitalists, alarmed by Whitlam’s allegedly radical policies and the US administration (through the CIA), disturbed by a less American-dominated foreign policy, were also involved. But the instrument of Whitlam’s destruction was the monarchy – and the monarchical constitution that enabled it. That instrument is still there, ready for use if things go awry for Australia’s rulers.

The official ‘republicans’ favour some sort of head of state who retains reserve powers of a monarch. Completely unacceptable for consistent democrats. We need no head of state, just a sovereign parliament or national assembly.

Beyond that, the republic is a fundamental issue of democracy, not just for Australia in general, but for the left and the working-class movement in particular. “The working class,” said Frederick Engels in 1891, “can only come to power under the form of a democratic republic.”

And yet, the Australian left tends to argue that this debate is of no interest to the working class – it’s just about tinkering with bourgeois rule. The debate is left to others because the left has lacked the imagination or vision to put forward a working-class alternative on how we are ruled.

This means that, in reality, the socialist sects merely tail behind the liberal bourgeoisie on constitutional questions. Witness their dithering over the Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum.

Only through a democratic republic can workers organise society in the interests of the overwhelming majority. For that reason, the immediate political task of the workers’ movement is abolition of the monarchy and its replacement with a democratic republic.

Beyond that, it is by championing high politics, leading the fight for democracy throughout society, that the working class trains itself to become the ruling class. That is why genuine republicanism is at the centre of the Marxist program.

We are not in favour of simply restoring the fast-fading Labor Party position. The minimalist presidential republic of the liberal establishment neither inspires nor suffices. Instead, what we need is a democratic constitutional convention with full powers to establish a provisional government and a new republican constitution.

We need a democratic republic that can:

- abolish the monarchy system and its constitution.

- reject presidentialism, monarchism’s undemocratic offspring.

- ensure election by proportional representation to a single legislative and executive assembly.

- abolish the senate, an undemocratic check on popular power.

- institute annual parliaments where MPs can be recalled and are paid no more than the average skilled wage.

- abolish the states and introduce meaningful regional-local government.

- abolish the standing army in favour of a universal and democratic citizen militia.